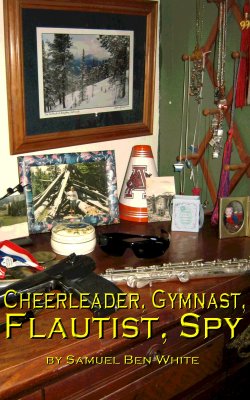

Laying in bed with a broken leg, Jody Anderson recalls the events that have brought her to that moment. Adolescent gymnast … college cheerleader … flute player in the band …

Just how did all this land her in a hospital, her medical bills paid by the Treasury Department?

How did she get from a farm in rural, northern Arkansas to the world of being a domestic spy, bullets flying, bones breaking, and romance?

Now available on Kindle and paperback! Now available on AUDIO!!

To read this story from Bat’s perspective, be sure and purchase “The Nice Guy“, “The Return of the Nice Guy“, “Up to Bat” and “Last at Bat“!

…

What the readers are saying …

“I read it and I loved it! Jody feels like someone I really met. Looking forward to more adventures with her and Bat.” ~KD, LA

“I like that you have given Jody her own novel. A very interesting character and I enjoy the relationship with Bat.” ~MM, TX

…

Sample Chapters

Prologue

I think my life turned a corner when I was sitting in bed one evening, looking at my leg. I wasn’t looking at the leg in the cast, but at the other one, the one that was—for that moment in time—my “good” leg.

I know some women who are really proud of their legs and other women who are constantly embarrassed by their legs. I don’t believe I have ever been one or the other. I never thought I had the prettiest legs around (or the most athletic, or most shapely), but I never thought they were the worst, either. Physically, I have good qualities and things I’m not thrilled with, but my legs? If asked—and I don’t think anyone ever has—I would probably have just said, “They’re OK.”

I was never quick enough with a glib comment, but if I were, maybe I would have paraphrased Honest Abe and said something like, “They’re long enough to touch the ground.” Or maybe I would have declared, “They get me where I’m going.”

Sitting there in my bed, pillows propping me up from behind and more pillows under what up until so recently had been my “good leg” in that it hadn’t been broken in a long time, my mind began to change. Not just about whether my legs were nice, hot, fat, skinny or ugly, but whether much of what I had held and believed was true.

It started with myself, though. And while I would like to think that I wasn’t so shallow as to be driven entirely by self image, I know my self image was a part of what was wrong with how I thought.

At that moment in time, I had one leg that was in great shape, but broken. The other leg was unbroken, but still a little atrophied from when it had been broken. As I sat there looking at my legs, I realized that the one that appeared to be worse off at the moment might be better off and the one that looked OK actually needed the most work.

As the days went by and I was able to rehabilitate—to force myself to rehabilitate—my focus went entirely to my legs. I was determined that both legs look good—not in a vain, supermodel way I told myself, but in a healthy, in-shape way—and in the process I lost focus on pretty much all else in my life. Still, the idea had crept into my psyche that evening that what appeared right wasn’t necessarily so and, as much effort as I put in to telling myself that truth only applied to my legs, the seed was planted that maybe it described the sum total of me.

To avoid that thought, I threw myself into my work and every workout, every exercise, even what I ate. I read articles on line and in print about the best nutrition for healing a bone break and for building back the muscles after a period of inactivity. I learned exercises I could do at my desk while at work, and more I could do in the evenings while watching TV or whatever. I devoured all the information I could find about the human body and how it heals after trauma …

And ignored pretty much everything I ran across about how the human mind heals after tragedy. I wasn’t interested in the mind. The mind, I told myself, was taking care of itself. It was taking care of itself by looking after the body, by exercising itself with reading and study (about the body, granted), and by putting the trauma of the past behind me.

I told myself I was dealing with the mental and emotional aspect of the tragedy by moving on. “Moving on” meant to me that I never thought of it and quickly changed the subject if anyone else brought it up. It was behind me and wasn’t worth worrying about. The now was what counted, and the future!

The amazing thing about seeds is also the problem with them. As a little girl I used to be fascinated with the way a tree could tear up a sidewalk. Here was this wooden thing that you could damage with an axe (or a bike, if you ran into it, while showing off in front of your sister … or boys), that you could cut up with a saw or burn with fire. And over here you had concrete which didn’t show the least little mark when you crashed your bike into it, that you couldn’t cut with a saw or set fire to. Yet, over time, that tree which had sprung from a tiny little seed—like an acorn—could destroy the sidewalk.

Once the seed got planted in my mind that everything was not as it seemed, it never stopped growing, expanding, working on me. And like the tree whose battle with the sidewalk may take a long time before it can be seen, it was a while until the seed in me grew big enough to no longer be ignored.

In the midst of looking at my legs as if I could will them into better shape or perform some sort of psychic surgery on them, the phone rang. I had a unit right beside my bed, but I didn’t answer it, preferring to let my family be my buffer zone.

A couple moments later, my father stuck his head in the door and said, “It’s him.” His hand was over the mouthpiece, of course.

When I didn’t respond immediately, just gave him a firm countenance that probably looked like I was constipated, he asked, “Shall I tell him you’re busy or to stop calling here or what? How ‘bout I tell him to go jump in the lake?”

I didn’t think of any smart remarks at that moment, saying at the time, “Just tell him I don’t want to talk to him.”

“Think you’ll ever want to talk to him?”

I avoided the subject by looking away and saying, “I’m kind of tired.” I hated lying to my father—or anyone, for that matter—but the seed hadn’t taken root, yet.

As he walked away, I heard my father saying, “She doesn’t feel like talking on the phone just now.” I marveled that my father was more truthful with someone he didn’t like than I was with someone I loved.

Chapter One – Gym

I spent the better part of four years as an only child. I don’t remember those years well, but I do have a few memories of having my parents and my grandparents to myself. I also remember that I spent a lot of time asking my parents for a baby sibling—preferably a sister.

“Be careful what you ask for,” they say.

Caroline Renee Anderson was born a couple months before my fourth birthday and, at the time, I thought I had gotten an early birthday present. She was a real, live, baby doll. The legend in the family is that I couldn’t say her name and called her “Carley”, which is what she was to go by all her life.

I have never been convinced whether I was a “Type A Personality” or a “Type B”, but whatever I am, so is Carley. In fact, whatever I did, Carley did it, too. When we finally got to be adults I came to appreciate what that said about Carley’s feelings for me—or maybe it was just because we spent adulthood in separate states. Until maturity (such as it is), though, Carley and I were constantly at each other’s throats.

No, that’s not true.

We were at each other’s hair. It’s amazing either of us had any hair left by the time we grew up.

The only time we weren’t at each other’s throat/hair, was when we were defending each other. I was horrible to Carley: incredibly bossy, insulting, condescending … but let anyone else give her the least bit of grief and they had me to deal with! She gave back everything I gave—even to coming to my defense against any and all outside agents. There were times when our parents wanted to keep us in separate towns just to have peace in the house, but we would both whine and even cry if we had to sleep apart.

I’m pretty sure we’re the reason our father is bald and Mom is gray.

I could give you a lot of facts about my childhood that would be true but would tell you very little about me or my growing up. I had some great grandparents on my mother’s side but never knew my father’s parents very well—owing to something in his life they were mildly disapproving of. I could tell tales of growing up in northern Arkansas in a rural setting, of chasing fireflies with my sister, of trying to tell people we had seen a bear, of just being a little girl. I went to school, I went to church, I went to camp. It would all be pretty typical, very true, and very unremarkable.

It wouldn’t, however, be about me. In my mind and (probably) in the minds of those who knew me, my life began in the autumn of my eighth year when my mom enrolled me in a six weeks course of gymnastics to see if I liked it. Liked it? I loved it. Gymnastics became my reason for existence.

I was attending a private Christian school back then. Even though neither I nor my family really had much interest in the religious aspect of the school, it had been chosen because it provided the best education in the area and better discipline than the public school. And I didn’t mind the Bible classes, just treated them as an extra Social Studies class.

The gymnastics class was held in the gym of my school, which was more of a bonus than I—as a child—realized, for it meant that my parents didn’t have to ferry me around to too many different places … except matches and competitions and stuff like that.

When I started gymnastics, so did Carley. I didn’t mind too much because we were in different groups and, once home, it gave me someone to talk shop and even practice a bit with who knew what I was doing.

I tried to talk shop to Mom, but she had never been around gymnastics until she enrolled us in that class and was behind the learning curve on the terminology. Looking back, I know now that my mother knew a lot more than I gave her credit for, but at that age I had the usual disdain for age and wisdom. At least, I hope it’s usual and I wasn’t just a stand-alone jerk.

The rule for the gymnastics team was that a C+ average be maintained at all times, but my parents demanded an A average of me if I wanted to continue. So my life revolved around school and gymnastics—and I only paid attention to my school work because it was my ticket to the gym. The teachers thought I was a model student, but I really didn’t give a hang about any of those classes.

Well, maybe speech, once I got to take it. I liked that class—and maybe English—because I have always been fascinated by the power of words. It was just a hobby—with gymnastics as a vocation—but it held my interest more than most other courses. I was good in math and history, but the bug never bit me for either. Music was always somewhat fun, but I never thought I had any special gift for it.

In junior high I was encouraged to go out for cheerleading, but I responded in much the same way as a fine painter might when asked to letter the neighbor’s garden markers. I saw cheerleading as beneath someone of my skills and was—looking back—pretty haughty in my dismissal.

I, I was sure, was on my way to bigger things. There was no doubt in my mind I was going to be an Olympic gymnast. In my more magnanimous moods, I pictured myself and Carley as making theU.S.team together and being on the covers of magazines and cereal boxes. With our auburn hair (inherited from mom before we made hers go the aforementioned grey), I pictured us wearing blue and white outfits and a headline above us that broadcast, “Red, white and blue!” I pictured gold to be included in that color scheme, too.

Superficially, I had some of the makings of a top gymnast. For one, I was never going to be tall, having topped out at5 foot3 by seventh grade and never getting any taller. I had strong legs and great balance. And I had drive.

Off the mats, I was quite the girly-girl, not the least bit of tomboyishness to be seen. I liked having my hair curled and I wore dresses and I never got in fights with anyone (except Carley). I didn’t rough house on the playground. I talked boys with the other girls, but didn’t slug them like the other girls (I’m talking about elementary, here).

Put me on the mats, though, and I was all focus. I did the exercises without complaining, listened to my coaches, and was determined to win every time I went out there. They said I was a fierce competitor, but I think that sounds wrong. I never had it in to hurt anyone else or really to even beat the other girls. I just assumed that if I did what I was capable of, I would win. In my mind, I was never beaten. I lost now and then, but it was always because of my own slip-up, not because someone else did better than I did.

Humility was not one of my strong suits. I probably didn’t even have a humility card in my deck. As least not when it came to gymnastics. I think deep down I knew I had weaknesses in the rest of life, but I didnt really care about those things. If they didn’t contribute to my Olympic dreams, I didn’t think they were worth much of my time.

Every day after school, I was in the gym until they kicked me out. Weekends we were at meets and in the summer I went off to gymnastics camp. I usually went to church camp with kids from school, too, but I spent most of the time with other girls who were interested in gymnastics doing tumbling runs and finding surfaces that could double as balance beams.

What I didn’t realize through all this—and didn’t really catch on to until I was well into adulthood—was that I had pretty much preempted my parents’ life, especially my mother’s. We didn’t take vacations like a normal family, because if I didn’t have a meet, then I had practice. When I didn’t have a meet or practice, which was rare, we were saving up for the next meet or some new piece of equipment I was going to need. For many of those years I harbored a latent grudge against my father because it didn’t seem like he was around, but the reason for that was that he was working extra hours to pay for all this.

Times two.

Carley was just as involved as I was and, considering she started sooner, was probably better than I was (not that I would have admitted it at the time).

If asked, we probably would have told a surveyor we were Christians, but the reality is that we were Gymnasts, for it was our real religion. The fact that we schooled and trained at a Christian private school meant no more to me than if the most convenient place to train had been a Zoroastrian monastery. I was there for the gym and put up with the rest.

Like all gymnasts, I had the occasional injury. Most of them were just minor strains, pulls and sprains, but in sixth grade I did break a bone in my hand that hampered me for several months. The crazy thing was, I could never remember when exactly I broke it. At the end of a practice one day I just mentioned to my mother that my hand hurt, so we put some ice on it, then when it didn’t feel better after a couple days Mom practically had to force me to go to the doctor. He couldn’t put me in a cast, but he wrapped it up that day and gave me strict orders to stay off of it for four weeks. I could still do a lot of things, but being prevented from anything was pure misery for me. Looking back, it probably wasn’t as miserable for me as I made it for my family.

Once healed, I was back at it full tilt. I was winning meets all over northernArkansasand, by my sophomore year of high school, I was already being watched by coaches from several major colleges. While I was still attending the same private school, I was competing in meets both for the school and as an “at large” athlete—a term I found very funny for a girl of 5-3—at competitions that featured mostly public school students.

Sophomore year I won best all-round in the Arkansas Association of Private Schools (AAPS) and placed second in the largest non-school meet in the state. I had worked hard and I was convinced everything was paying off. I had excellent grades—which I didn’t care about except that they kept me tumbling—though I was learning that good grades really impressed the college coaches. I wasn’t above dropping my grade point average into conversation if I thought it would help my gymnastics career.

My right elbow had bothered me some that year, but not a whole lot. Just enough that I was always aware of it, but not so much that I told anyone. Bright, huh? After the all-state meet, I mentioned it to my mom, who quickly got me a doctor’s appointment. In theory, I had some time off before I would be gearing up for my junior year and, if I had to take some time off to let something heal, that was the time.

I figured it was just a mild sprain, maybe stress from all my working out, and thought some time off (which, in my mind, was a couple weeks—max) would help. So I consented to going to the doctor just to humor my mom. The doctor checked me over and seemed to be of an opinion similar to mine, but he sent me in for an x-ray on my arm anyway. It turned out there were some tiny little cartilage chips in my elbow region that were the culprits. He scheduled me for surgery, dad’s insurance paid for it, and I thought my life was over because my elbow was immobilized for four weeks, and then restricted to limited use for four more weeks after that. That meant I was going to just barely make it in time for the beginning of the next season, but I determined that I would work my legs and my left arm during the first four weeks, then follow the instructions to the letter for the right arm. I told myself this would, in the long run, make me a better gymnast.

Carley, meanwhile, was excelling at gymnastics and—at eleven years old—was at or beyond where I had been at eleven. We pushed each other until … well, you might say we pushed each other raw. When we weren’t hugging each other and congratulating each other on a successful routine, we were shouting at each other and, sometimes, even coming to blows. How our parents stayed together with all the stress Carley and I put on them I don’t know to this day.

I spent one of my four weeks of convalescence at church camp, and another at band camp. One of my coaches, back in seventh grade, had said that I needed to find an outlet that had nothing to do with gymnastics. I thought it was a crazy suggestion, but I took everything she said as gospel. I think she tried to steer me into painting, but I had absolutely no artistic talent. At church camp that summer, though, I got to be friends with a girl who played the flute and she taught me a few notes. I decided I liked it and, when I got home, asked the school if I could borrow a flute from the band supplies and then signed up for lessons.

I was only ever a mediocre flute player, but I discovered I liked it. I hadn’t taken it up specifically to drive my parents or sister nuts, but I think I did. I discovered that my favorite way to study for a test was to sit on my bed, with all my notes arrayed before me, and play my flute. Then, when I would go in to the test, I would hum the tunes I’d been playing in my head and the answers would come right to me. In high school, I tried out for the band and eventually made first chair flute. I still say I was mediocre, but I was accurate. What I mean is: there are flute players (as with any instrument) who can really bring a flare to their instrument. I couldn’t necessarily do that, but I could read the music and play it—exactly as written, granted, but I could play it. No improvisational skills whatsoever. This made me a wash at jazz band, but a success for the concert band.

Classes, gymnastics, then an evening playing my flute while I studied. I had so few social skills I was the kid the nerds made fun of.

About the only other thing I ever did was shoot guns. Not that I would have ranked it up there with gymnastics as far as an interest, but my father had started taking me to the gun range when I was twelve. With all the time I invested in gymnastics—which involved myself, my mother, and Carley—I think my father was feeling a little left out. So he determined that he was going to “do something” with each of his girls. Carley he took fishing and me he took shooting.

I did enjoy the time with my father—and in retrospect wished I had paid more attention to him and let him know I appreciated it—but my mind was mostly on gymnastics or school. Still, at least twice a month my father would take me over to the gun club where he had been a member most of his life and he would teach me how to shoot. I was never more than passable with a rifle—for what reason I have no idea—but I could, as my father said, “shoot the lights out of anything” with a pistol.

I came to prefer a “nice little” semi-automatic Ruger he had purchased over all other guns, but was also proficient with an old west style Colt .45 that had belonged to his grandfather. For a brief period I tried to use his .357 Magnum but it was just too much gun for my strength—even as I got older. Balanced on the shooting range table I could fire it accurately, but I could never do well just holding it free and, so, would go back to the Ruger. Some of the other members of the gun club used to try to encourage me to enter some shooting competitions but—as much as I liked to compete in other things—I liked keeping shooting as just a fun activity with my father. My father never pushed me and I got the impression it was because he felt the same way.

Junior year, I did really well in the fall meets and led my school to a state championship in women’s gymnastics. By the spring semester, though, my right arm started hurting again and my left was beginning to mirror it. I tried to tough it out, but I finished up third in the all-round for the AAPS. After I got past the tears—not from the pain, but from losing—I told my mom maybe I needed to go to the doctor sooner so that I would have more time to recover for my senior year. I was sure scholarships were in my future and was still holding out hope for the Olympic team.

I went to the doctor thinking he’d just “scope” my elbows and tell me to lay off things for another eight weeks. I figured I would keep working my legs and maybe even do a second week of band camp—focusing on the marching aspect. I even toyed with the idea of taking the youth minister at our church (we spent so much time there during the week we’d started showing up on Sundays, too) up on the offer to work at church camp but couldn’t figure what I would do with both arms in braces.

For years, I could remember nothing of the week after the visit to the doctor. I was not just in a funk, my world and vision had gone black. I look back and I’m really glad I didn’t wreck my car or take up alcohol or something.

We had gone to the same doctor as the year before, but after looking at the x-rays he had sent us to a specialist in Little Rock. There, after another round of x-rays and anMRI, the doctor came to where my mother and I were sitting in a little room and she pulled up a chair in front of me.

She held out some papers with pictures on them and, circling some little bitty dots that appeared near my elbow, said, “Jody, I’m afraid you have what’s technically called ‘Panners Disease’, though it’s commonly known as ‘Little Leaguer’s elbow’ or ‘tennis elbow.’”

I breathed a sigh of relief and concluded, “So I just rest it and it’ll heal up, right?”

The doctor looked at my mother, then at me, and pointing to the little dots she had circled said, “These are pieces of cartilage, Jody—“

“That’s what I had last year,” I injected, figuring I was about to embark on another 8 week layover in my life plans.

The doctor, a too-early-matronly, middle-aged woman with long hair tied back in a pony tail, shook her head and said, “It’s not that simple. We can clean this up—and I would recommend that you let us do just that—but your right elbow may never be at one hundred percent again. You are one in a million, Jody,” she told me with a forced smile.

“Meaning?”

“Your left elbow is on the same path, which is something almost never seen: for one person to get this in more than one joint. Now, it’s not a guarantee that your left elbow has Panners Disease, but it looks to me like it is heading that way. If we do no surgery, besides the pain, your elbows might start locking up on you.”

The mental imagery of that happening made me cringe—and I noticed my mother having the same reaction. “And what would have to be done to unlock them?”

The doctor hesitated, as if formulating her words, then said somewhat cautiously, “It might never happen. But if it did, the most likely scenario is that you would be doing something in gymnastics where there’s a lot of stress—a routine, for instance—and you would straighten your arm and not be able to bend it.”

“Stuck straight out?” I asked, really recoiling at that imagery.

“I don’t mean straight out. It’s like,” she demonstrated with her own arm, “I hold my arm out and it locks in this position. Then, I can bend it a little, maybe a couple degrees, but that’s it. At that point—see, one of the big problems is that if that happens, a person usually panics. Really, all you’re going to need to do for—say, ninety percent of the time—is just try your best to relax as you bring your elbow back to a completely straight position. Most of the time, you’ll be able to bend it normally again after that.”

“And the other ten percent?” my mother asked, worry thick in her voice.

She smiled comfortingly and said, “More like nine and a half percent. In those cases, the locked up person—you, in this case—would hold the arm out straight and, with the other arm, try to rotate the stuck arm very gently back and forth. A few moments of that and you’ll bend like normal again.”

“And that half a percent?” I asked timidly, worried what horrible thing might be left for the “lucky few”.

The doctor smiled and said, “Honestly? It’s probably less than that. But in those cases, you might need to seek a doctor’s help. That’s rare, though. I once had a patient have this happen to his son and I was able to walk him through unlocking it over the phone.”

“Seriously?” my mother asked, mortified at that idea. (And I wasn’t thrilled.)

“That was his reaction,” the doctor replied with a friendly laugh. “But it was actually very simple and it almost never comes up.”

“So what do we do?” my mother asked, seeing that I was dumbfounded.

The doctor took a deep breath, then said, “I recommend the surgery. And then, I recommend that you give up gymnastics, Miss Anderson.”

The rest of the visit and several days after that are a complete blank for me. Two weeks later, when school was out, I had the surgery on my right arm. I went to church camp and cried and prayed and nothing changed, so after band camp I had the surgery on my left arm and then I went home and threw all my gymnastics stuff in the trash—even the trophies and ribbons. My mother had seen all this and—I was to find out later—had fished it all out of the trash, boxed it up, and presented it to me later (a couple years later) when she heard me lamenting having thrown it away.

I lay in my bed that evening, having already made it clear to my parents that I wanted to be alone. Carley was either slow on the uptake or refused the notices because she came into my room and, without saying a word, lay down on my right side, put her head on my shoulder and cried with me. When we stopped crying we just lay there like that, not a single word spoken until our mom found us laying side by side in the morning—still in the clothes of the day before. I hugged Carley with my good arm, told her she was the best sister ever, and vowed to never fight with her again.

I kept the pledge for almost two whole days.