This is where Phil is reading “After Time Ends”. How about you?

This is where Phil is reading “After Time Ends”. How about you?

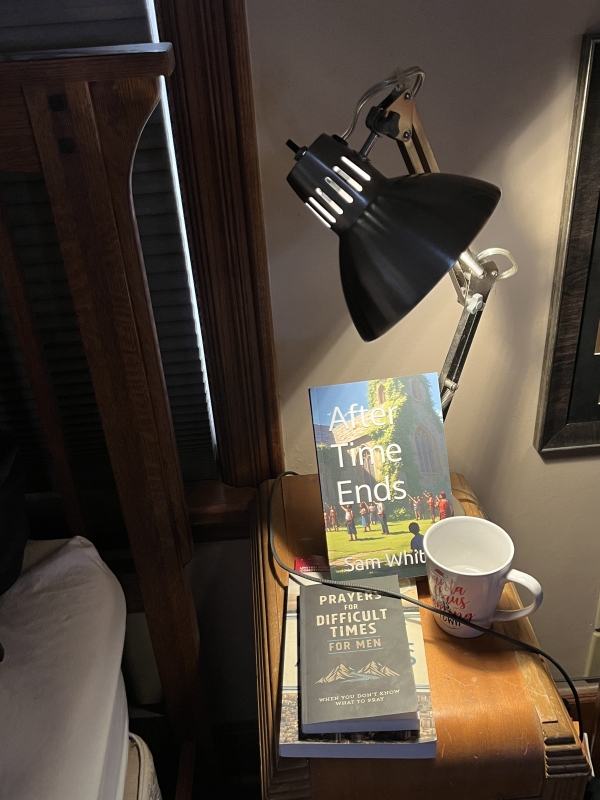

Available Now on Kindle, paperback, hardback and more formats! Now available on many other formats!

Gabriel’s trumpet has sounded.

In a flash, the wicked have been swept away and only the saved are left. All aches and pains and worries are gone, but this isn’t what those left were expecting. It’s not what they had been taught.

One by one, the saved are finding themselves drawn together; in praise, in worship, in Scripture. The children aren’t children and the elderly are no longer old. There is no more sorrow and no more death.

What comes next?

And where is the Lord?

Sample passage

Clarity woke up suddenly, thinking she had heard some incredibly loud sound, but sitting up in bed with her heart pounding she couldn’t remember what it was. A car back-firing? The city’s tornado sirens? She had no idea and, if a siren, it wasn’t blaring now.

Looking to her left, she was surprised to see that the bed was empty. Had he heard the sound, too, and jumped up to go see what made it? Had someone broken in? Had something fallen somewhere in the house?

It was only then that it registered on her just how light it was outside. As she rubbed her eyes, she mumbled, “Just how late is it?” She glanced over at the clock but it’s face was dark. No numbers, nothing. She glanced up and saw that the ceiling fan wasn’t turning.

“No power,” she muttered. As she got out of bed and put on her summer robe, she assumed then that the noise she had heard was probably what had knocked out the power. Maybe someone had plowed into that transformer on 44th. That seemed the most likely, for there were frequent crashes and fender-benders on that street. How long had it been since that motorcyclist had been hit and killed? Two months? Three?

Stretching, she then walked out into the house calling, “Tim? Are you up?

“Of course he’s up,” she chuckled to herself. “If he weren’t up, he’d still be in bed.” She knew that wasn’t true, for some nights he couldn’t sleep and went out to the living room to watch TV or read and then fell asleep in the recliner.

But no voice answered in return.

Clarity glanced into the guest bedroom as she passed it, for he sometimes slept there rather than come back to bed and wake her up, but no one was there. The home office was equally bereft of occupants. “Tim?” she called again, seeing that no one was in the living room. Neither did any sounds come from the kitchen. The back deck, pleasant at that time of year, was empty as well.

It was coming on to summer, so maybe—she reasoned—he took off early for his daily walk. When she glanced out the window and saw that both cars were there, she nodded, thinking that had to be it. He just went out on his morning walk and would be back at any time. He had done that before. And while he was usually really careful about closing the front door as he left, she was betting the wind had jerked it out of his hand and that was the loud noise she had heard.

Stretching again, yawning, she went to the fridge and pulled out the milk for her cereal. Even knowing that the power was out, she was still surprised when the fridge was dark inside. She laughed at herself for that.

As she sat down to eat her bowl of frosted wheats, she noticed that Tim’s phone was still on the counter. She frowned, but not really with worry. She was always reminding him to take his phone with him when he went on walks. He had never, in all their years of marriage, needed to call her from a walk, but she always wanted him to be able to, should he need to. The truth was, she admitted, that she had always wanted the ability to call him, though that need had rarely arisen. (And the times of “need” were a loose definition of the word.)

“Oh well,” she said with a chuckle and a shrug. He would be back in a bit and she’d give him a light-hearted scolding and he would say, “I’m fine, see?” and they would both laugh at her worry.

Breakfast came and went, though, without his return. She rinsed her dishes and then headed to the bathroom. She left the bathroom door open so she wouldn’t have to shower in the dark, but she still hastened through the ablutions for some reason. “Who am I expecting to walk in?” she asked aloud, with a chuckle. The kids would all be at work by that time, so she need not worry about one of them dropping in—not that they had ever dropped in that early anyway, even when they had lived in town.

When she was dressed and he still hadn’t come back, though, she thought she ought to go look for him. Surely nothing had happened, but if something had, he had no way of calling her. She was betting he had been outside when whoever had plowed into the transformer and, like a little boy, was over there watching the police and firemen and people from the electric company take care of the business at hand.

“But there haven’t been any sirens,” she mumbled aloud. In fact, she thought to herself, I’m not hearing any traffic. The house had new, double-pane windows—put in just last year—and while they had cut down on outside noises considerably, they hadn’t eliminated them entirely. She wasn’t hearing anything, though. Normally, there would be the sound of at least one hopped-up ride on the main street a block away, or just the dull hum of traffic in general.

And it was Tuesday. Shouldn’t she have heard the trash trucks by now? And all the dogs barking at the trash trucks? Even her wonderful windows couldn’t completely eliminate that!

She decided, then, to make up the bed and, if Tim weren’t back by the time she was done, she’d go for a walk herself. She’d head for that transformer first, she determined with a smile, sure to catch all the grown-up men of the neighborhood watching the heavy machinery like little boys. Some of them with their little boys in hand.

She picked up Tim’s pillow and, beneath it, there lay his wedding ring. She picked it up curiously, noting within herself that there were no thoughts of panic or approbation. Just curiosity.

With the ring still in her hand, she pulled back the covers so as to straighten the sheets—how Tim could wrinkle the sheets for a guy who rarely ever moved once asleep!—and there were his boxer shorts. She started to reach for them, then realized they were right where they would be if—

And the ring. He often slept on his stomach—as the shorts would indicate—with his hands under the pillow. The ring was right where it would be if—

Slipping the ring into her pocket and her feet into her shoes, she rushed from the bedroom and out of the front door. Down the steps and into the yard, she looked around and …

Didn’t see another soul.

No one. That the neighborhood would contain empty front yards was not strange, for hadn’t she and Tim both remarked over the years that people just didn’t hang out on front porches anymore? Some even had furniture on their front porches—nice little matching chair and table sets—but she could count on one hand the number of times she had seen people sitting thusly. People came out of their houses just long enough to get to their cars, or go from their cars to their houses. If no one were mowing, no one was in their yard. There were lots of times when she had gone out herself and seen no one else.

But there were no cars moving along 44th, one of the city’s major arteries. And there were no sounds of cars in the distance, or airplanes. Or much of anything else. No machinery at all. No air conditioners spinning. The only sounds she was hearing were that of a few birds, maybe one distant dog barking, and the sound of a sprinkler three houses to the north.

She looked at the sprinkler and watched it spin for a moment. Just a simple, old-fashioned sprinkler on a hose. But it, the wind, the birds and that one dog were the only sounds she could hear. Now there were two dogs barking, but neither seemed frantic. Just the normal greeting of dog to dog.

And yet, she wasn’t afraid. She thought maybe she should be, but she wasn’t.

“Tim!” she called loudly, and then again.

There was no answer, from anyone.

“Maybe I’m dead,” she said, in a normal, casual voice. The thought didn’t scare her.

She was curious, though. What was going on? Where was everyone?

“Surely I’m still asleep,” she said with a laugh. “Yeah. I have to be.” She took a few steps out onto the grass of her front lawn and said, “Yeah. That’s got to be it. Doesn’t feel like a dream—feels too real—but it’s got to be a dream. If this were real, there would be stickers,” she added with a chuckle.

“What else could it be?”

She dropped to her knees and began to pray, but didn’t know what to pray for. She realized, though, that she knew what had happened and where Tim was. With perfect clarity of mind, Clarity still found herself weeping, wondering what she could have done differently, while still praising God for his sovereignty.

Available Now on Kindle, paperback, hardback! Also available on Smashwords and Nook, Kobo & more!

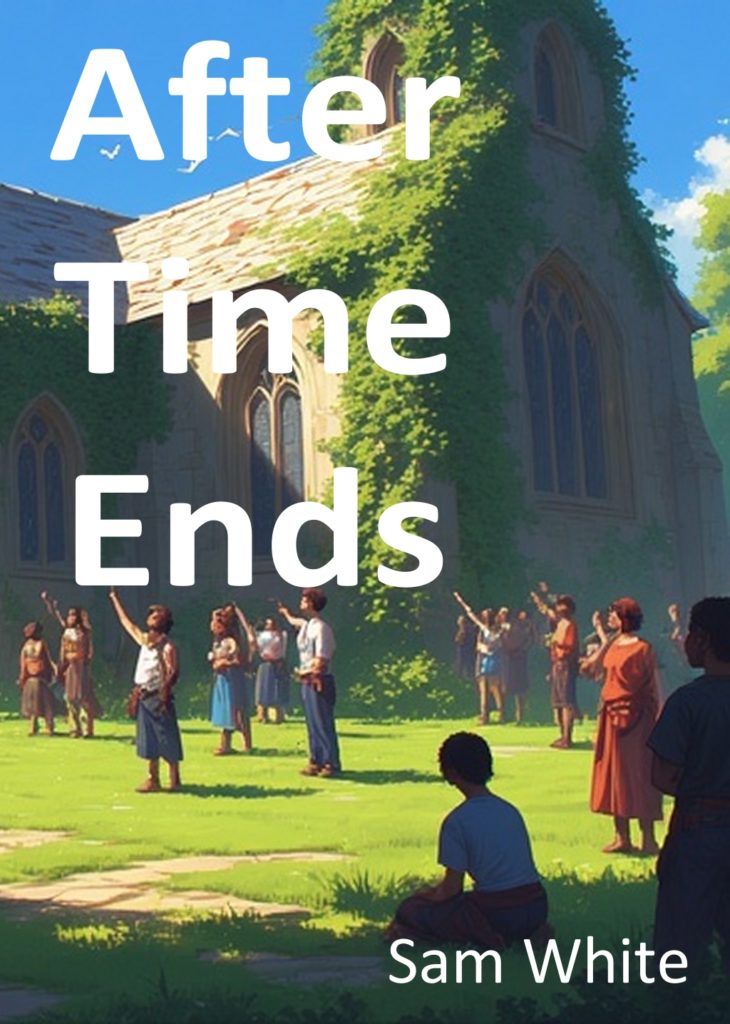

A world without sin or strife or pain.

Scott Passer III, “Trey” to his friends and family, went in for a routine heart ablation. He woke up in a spaceship little bigger than a coffin and going … where?

He finally crashes on an idyllic planet many galaxies away the locals call Oolod. They put him back together and begin to show him a world where no one even knows the meaning of lie.

And hovering over all is a mysterious figure Trey can’t see. He can’t even hear the being’s name when others speak it. Who is this strange being, and was it him that brought Trey across the universe?

And why?

$2.99 on Kindle and $12.99 in paperback. Order yours today!

Sample Chapter

I went into the hospital for just a routine ablation. I mean, as routine as those things can be. They are attempting to get an out-of-whack heart back in whack by searing it and causing scar tissue in just the right spot. Yeah, it’s as crazy as it sounds, but it works.

And since you’re looking up what it is on line anyway, I’m not going to knock myself out explaining it to you.

As far as heart surgeries go, it has a history of success. A lot of people are back at work within weeks, sometimes days. For some people it takes a little longer, but not usually too long. Not like a lot of the other heart surgeries.

And I had had it done before. A couple years before I had had it done at a hospital in Oak City. The thing was, though, they could only do so much of it at one time, so they did (according to them) about ninety percent and then the plan was to get the remaining ten percent “in a couple years” after I was completely healed. (Yeah, I know I said that they said that most people recover quickly, and on the first round I had. I had gone back to my job as an accountant after a couple weeks—part time—and then full time by a month later. Not like I was playing pro sports or prone to ridiculous amounts of jogging, so I didn’t have a problem.)

I just had to get the job finished. Afterward, they told me, I would be back up to full strength in no time. All the old fatigue gone, better sleep at nights, a new man—if you didn’t count that I was rapidly leaving fifty in the rearview and hadn’t been a stud on any field or court since, well, ever. In Little League I was the kid you stuck in right field, in adult softball I was the man you put at second base or catcher—the two places least likely to harm the team in a no-slide league.

So maybe, with that final ten percent taken care of, I would at least be able to go on a long, brisk, walk without feeling light-headed or nauseous.

When I had it done before, I went through all the pre-test junk we’ve come to expect, filled out a ream or two of papers, then showed up at the hospital on the day in question. I was well-rested because my insurance had even sprung for a decent hotel room near the hospital for the night before and after the surgery. I hadn’t eaten or drunk anything in twelve hours when I walked through those hospital doors and, pretty soon, I was laying in a hospital gown on a hospital bed, thinking hospital thoughts.

They had wheeled me into the operating room and then this nice lady had told me she was going to put some stuff into my IV which would make me go to sleep. I started counting backward from a hundred, got to about ninety-seven … before waking up in recovery and being kind of sore and tired. It turned out, they had stopped short because the anesthesia had been wearing off and they couldn’t have continued without putting me in serious pain, the kind of pain that would have complicated my recovery.

That’s what I was expecting, then, for round two: count to three, wake up in another part of the hospital, everything hunky-dory.

Anytime you go under, though, there’s always a slight chance you won’t come back up. Or that you might have a wild dream while under the influence. The kind of dream that seems so real you will never be convinced by anyone that it was not.

The Journey

I’ve always been a man who followed his instincts. When I woke up, then, and my first instinct was to scream, that’s what I did. Instincts two through six were remarkably similar, so I followed them as well. Instinct seven was to call ineffectually for help, so I did that, followed by more screaming.

You see, I had expected to awaken to the visage of the anesthesiologist who had put me to sleep—or one as like that one as to be no matter—and then get the usual questions like “How are we feeling?” and “Would you like something to drink?” When I didn’t wake up to that, I think my responses were quite called for.

At first, I thought I was still asleep, for it was all darkness about me. But then I realized my eyes were open for I was seeing a little. Dim shapes and faint lights were all about me. Hence the screaming, though, for I appeared to be in a box. My first thought was: coffin. “I died on the table and now my heart has re-started on my own but they’ve already chucked me in a box for shipping back to … where would they ship me?”

I was born in Flomot, Texas—wait, that’s not right. I was born in Lubbock, TX, but that was because there was no hospital in Flomot. One of my first sensations upon awakening from the anesthesia was of movement, which is what helped lead me to the conclusion that I was in a coffin and someone was taking me back to Flomot for burial. I didn’t have any special affinity for Flomot, but I guess I never had made any “final wishes” known, so it made sense to bury me near my mother’s plot. They could have buried me near my father, but he was a veteran and accorded such honors, so I would only have been in the same pasture, not right next to him.

Once past most of the screaming, it came to me that if I were in a coffin, there wouldn’t be any lights. I had seen coffins advertised that were insulated so you could buy them before you needed them and use them as coolers at parties before you checked out, but I had never known of one that came with lights. And these lights didn’t seem close enough to be inside the coffin with me. Where were they coming from?

Trying to calm down and think about the problem, I hit on the idea that maybe I was inside an iron lung. I had never heard of winding up in one being one of the possibilities following ablation, but then I also had no idea what an iron lung looked like from the inside or out and, thus, the theory was no better or worse than any others I might have come to.

I tried to move my arms and legs, but while I could move them a little, I was clearly packed into some sort of … something? Box? Coffin? Shipping crate? I think my mind liked the iron lung idea because it at least connotated medical care whereas all the other options led one to think of abandonment.

Maybe it was some sort of hyperbaric chamber, I suddenly thought. I had heard the term and, while I didn’t know any more about what one looked like than I knew about iron lungs, the idea seemed more reasonable. Didn’t they use them to immerse someone in a very sterile, pure environment? Maybe, I reasoned with my still-panicky self, there had been some hint of infection and they needed me in a completely clean environment as I recovered.

With that thought in mind—and realizing it could still apply to what little I knew of an iron lung—I decided that maybe I was looking through a glass window at a darkened room in the hospital. Not one hundred percent dark, but just mostly darkened. Why would it be so? I asked. Perhaps it was late at night. Or maybe it was just part of providing a calm world for the patient to wake up in. Bright, garish, hospital lights can be rather unsettling, I knew, when one first woke up.

But then, I realized the lights were moving. And that there were a lot more of them than I had at first thought.

Stars!

I was looking through a window at stars!

And either they or I were traveling very fast.

I actually calmed down then, for it became instantly clear to me that I was having a dream. It didn’t feel like a dream, but I just guessed that to be because of the drugs. As I noticed the stars (or me) moving faster, I laughed to myself that the anesthesia should have included some Dramamine.

I also got the sense that I was accelerating away from Earth—flat on my back and feet first. I couldn’t turn around and look, of course, but that was just the idea that came to my mind. I looked for Saturn, but was already outside the solar system and moving away quickly—or so I calculated (with no available facts).

Order your Kindle copy today! Click here. For the paperback, click here!

AD 5252 and all of the western world is at war.

Led by King Vykyant, a coalition of more than a dozen nations has come together to fight an evil on a far-off continent. “We will fight it there to protect our families here.”

But the families at home are not free of danger, for the fight is being waged there, too.

Thousands of soldiers marching, fighting and dying in a foreign land. People at home getting spotty information at best.

A world at war, as told through the eyes of the people on every front line.

Now available for Kindle & paperback. (Due to the length of this novel, it will not be available in hardback.)

Sample Reading

Three thousand years before, the continent had been a land with everything: verdant forests, wide rivers, harsh deserts. There had been cities and towns and beaches and places where men and women went for leisure and many places where they worked. It had been a land of mystery, and legends, and ghosts.

There had been people of education and what was called sophistication, often living just feet from those who didn’t receive those accolades. There had been people in the finest clothes, often living not so far away from people who had the barest rags, then a little further away were people who didn’t know what clothes were for and—had they known—couldn’t have imagined wearing them. Technology had existed side-by-side with stone tools.

When the first of great wars had come, the majority of the continent had remained relatively unscathed. Relative being a relative term, for there had been fights and squabbles, but almost none of the large-scale harm that had affected every other continent on the planet. Some of the survivors from other continents moved to that continent thinking it would always be that way.

When the wars returned—though in the myopic view of the future’s rear view, all the wars were one—the continent was mostly spared, though circumstances made it isolated.

The continent was still rich in many ways, but especially in tyrants and graft. Its resources were plundered and sold, leaving the majority of its population in even more poverty and want than they had been before—and they had been among the planet’s poorest back then. Its great forests were plundered not just for the wood, but for the precious metals that lay beneath, a process that had begun before the wars, then accelerated after even though the booty was just being sold to fellow residents of the continent.

But then came more wars that finally poisoned the rest of the planet. That southern continent was more protected than all the others, or so it seemed at first. Very few military strikes landed there. It was not attacked with the poisons that were levied against practically everywhere else and atmospheric conditions swirled them away. The last of the people who could escape from the other continents came to the southern continent.

They brought their wealth with them—some of which had come originally from that continent, ironically. The richest brought their own security forces with them, setting up little fiefdoms, assuming that to do so was their right even as they ran those who had been on the land for time out of mind off of it. Those so displaced headed to the already crowded cities, making life even harder—or deeper into the jungle.

And then the winds shifted. Not the political winds, but the actual winds, and the poisons everyone thought they had escaped came to the southern continent.

Millions were wiped out in just months’ time.

As in the rest of the world, those who survived, survived in pockets. Perhaps more people survived on the southern continent than on others. Some estimated that while elsewhere in the world ninety percent of the population was wiped out by the wars and their poisons, on the southern continent it was “only” eighty percent. Those who survived quickly stopped burying their dead and just threw them into the rivers or natural ravines. This exacerbated the poison, and the stench.

Technology was lost.

Commerce between the pockets was impossible.

Mankind was reduced to its most primitive state as every waking hour was spent scrabbling for food and shelter. And on that continent, in its pockets, there were more people fighting for the few resources the poisons hadn’t killed. The men and women of those lands became more vicious than in the rest of the world because they had to if they wanted to survive.

A millennium later, as the poisons dissipated and people all over the world began to venture bravely beyond the piece of ground they had known for a thousand years, there was some conflict of course, as is the nature of man. In some places there was cooperation, though, as the people met others who had goods or services they didn’t have themselves. In some cases across the globe rival pockets still spoke a semblance of the same language, but in some they were so divided they couldn’t even sign to one another. There was fighting at times, too.

The southern continent knew nothing of cooperation. For a thousand years and more, all anyone had known was a mad struggle for life amidst death and when they encountered someone they didn’t know, the first thought on every mind was challenge, and murder. Pockets of stronger people conquered pockets of weaker people, though there were no pockets of weak people. The strongest took over, killing or enslaving the weaker until only the very strongest ruled. Tin-pot dictators were overrun by tyrants, and tyrants were squashed by despots. When finally a potentate arose for a time who was over the whole continent, it was with an army of people who were only biologically men, for in reality they were animals.

Like with animals, as the leader began to show weakness, he was slaughtered by a younger, stronger, lieutenant who would then rule until the same fate befell him. And so it went. For two thousand years the plants grew back, deformed and twisted from the lingering effects of the wars, but not so deformed and twisted as the men and women who occupied the lands.

Their languages were guttural and rarely written down. Their thoughts were of conquest and survival and not worth being written. Every thought was toward evil and their own advancement.

It was only natural that the puppet who was the latest to rise to “command” of the whole continent could be easily persuaded to look beyond the continent, to the lands to the north, where it was said there were good lands and weak people who would fall easily before his blade.

Ash.

Siblings Josh and Claire were out with a detail of locals trying to replant the Selkirk area following the previous summer’s fire when the ash hit. They had seen a lot of ash, but not like this. This was a wall two miles high that swept through and buried everything. Everything.

Some said it had to be the result of a volcanic eruption. As far as anyone can tell, the two-score people who have made their way to the valley are the last people left alive in the world. Everyone is trying to survive, but Josh is determined to thrive.

With Claire by his side, he begins to rally the people to not just claim a life in the ash, but to build a new community. With death all around them, and continuing to come their way, Josh begins to wonder if he can keep everyone going long enough to build something new. Even if he can keep their hopes up, how long can they push back against the ash?

From the ash arises a new town, a new way of life, and hope.

Be sure to read the rest of the story in “Crazy on the Mountain” and “Book of Tales“!

Available now for Kindle and paperback.

…

Sample passage

You can only live in panic so long. Eventually, you have a nervous breakdown or you wear out. Claire and I just wore out. It had been about six o’clock in the evening when the wall of ash descended on us and minute after minute, then hour after hour, of sitting in a darkened pick-up truck, clinging to your sibling for dear life, while outside the wind moans and nothing is visible takes its toll. Throw in that we were already tired from an afternoon of work and, somewhere in there, we fell asleep. Or my brain shut off, which was a lot like sleep.

I remember having the momentary thought that I probably wouldn’t wake up. I pictured the ash covering the truck until every crack was full and the air was used up. I fell asleep picturing our parents crying one day as they got word from the Forestry Service or someone like that, saying that a pick-up with the remains of their two youngest was found buried under a mountain of ash. I look back now and am a little surprised that I fell asleep under those conditions, but at the time there just wasn’t anything else to do.

“Josh,” a voice whispered in my ear. I hoped it was my mother, waking me up in my own bed, the events of the day before just a dream.

“Josh,” repeated Claire, a little more loudly. “I can see.”

“Hmm?” I asked, trying to wake up and realizing just how uncomfortable sleeping upright in a pick-up truck can be. I finally got my eyes to open and realized Claire was right: we could see, if dimly.

The wind was still blowing a hefty breeze, but the cloud of ash had dispersed enough that we could actually see a little of what was outside. It was a weird light, though, and it took me a few more moments before I realized that what I could see was because the moon had broken through a gap in the clouds—whether clouds of water vapor or of ash I couldn’t tell at that moment in time.

As my brain came into focus with my eyes, I realized that part of why we could see—even by the light of a not-full moon—was because the moonlight was reflecting off the light-gray coat of ash that covered everything. It wasn’t quite like moonlight on snow, but it was a little brighter than if it had just been shining on the dirt. “Wonder what time it is?” I mumbled.

“Middle of the night, looks like,” Claire responded. “We must have slept several hours.”

“I’m just glad to wake up,” I told her. She cast me a strange look, but didn’t ask me to explain.

“Think we can drive home now?”

“Maybe. I can see the road, anyway. Wonder if we ought to check and see if everyone made it to safety, though?”

Claire looked like she was about to say something in response to that, then pursed her lips and nodded, saying, “You’re right.” She pulled a flashlight out of the glove box and checked to make sure it worked. She started to reach for the door, then gave me an ironic smile as she gestured with the flashlight, “Why didn’t we remember this earlier?”

“Just geniuses, I guess,” I replied with a shrug.

The wind was blowing, yet not really high like it had been when I had gone after the bottled water. Still, as soon as we were outside and next to each other, Claire took my hand as she swept the area with the flashlight in her other hand. If memory served, the last time she had held my hand for anything other than a family prayer was when we were both pre-school age and Mom had made us hold hands while we crossed the street. It was a strange sensation and not particularly comforting to me, but maybe it was to her. Just as I thought that, she gave my hand a reassuring squeeze, then let go.

The ash beneath our feet stirred up with each step, making us cough even though the makeshift bandanas were still in place, and then making us go slower so as not to stir so much up. It wasn’t deep—perhaps no more than a half-inch to an inch in most places—but it was pervasive. The wind kept ash in the air, but another glance up at the moon showed me that we were in a sort of trough where “new ash” (like new snow) didn’t seem to be falling. The ash in the air seemed to have just been stirred up from the ground or been blown off the ridge that hung above us to the west. To the north and south, on either side of the gash in the sky, it looked like the ash still roiled.

We walked nervously over to where the flashlight showed us a lump under the ash. Claire held back a step but curiosity forced me to close the distance and kneel down, even though the shape beneath the ash was pretty clear. I reached out gingerly and brushed the ash away, hoping I would startle whoever it was awake.

The body was cold beneath the ash.

“Can you tell who it is?” Claire asked, coming a half-step closer.

“Annie Meyers,” I replied, then wishing I had a way to cover her face back up with a blanket, or the ash. A muffled sob escaped Claire’s lips.

“If we had … “ Claire mumbled.

“Yeah. If we had known, and if we could have found her, and if we could have brought her into the truck—“

“You don’t care that she’s—she’s dead?”

“Of course I care. And I will spend the rest of my life telling myself I should have seen her and picked her up but I’ll also spend my life knowing there’s nothing I can do to change the past.”

“Why are you so cold?”

I stood up and responded angrily, “Cold? Claire, look around you. There are at least three other lumps in the ash about the same size as this one was. I’m not cold, I’m … I’m scared to death!” I was a little surprised at my ability to say it out loud, but once having said it, I knew it was true.

She came over and, putting an arm around me, offered, “Maybe someone else made it to a vehicle.” I nodded and we began to gently step towards the nearest vehicle, an old van owned by Mister Glass.

I pounded on the side of the van and was both startled and relieved to hear a response. The side door of the van slid open and Mister Glass stuck his ash-covered and bespectacled face out into the wind. “Josh? And Claire. How have you survived this long?”

“We were in our truck,” I replied. Claire shined the light into van as I asked, “Did anyone else make it through with you?”

“There are five of us,” Mister Glass replied, stepping outside and looking up in apparent surprise at the moon. “I think the others are asleep, but I haven’t slept a wink. Anyone else make it?”

“We don’t know, yet. We know that, um, Mrs. Meyers didn’t.”

Mister Glass swore lowly, then said, “I got a couple lights. Let’s see if we can find anyone else.”

Howard Glass was a semi-retired electrician from Kansas who had come to the mountains with his wife a decade before. She had died of cancer a couple years after they arrived. He always talked about going back to Kansas, but he also talked about how much he loved the mountains. When he lost his house to one of the fires, we all figured that would be his signal to head back to the flatlands. Instead, he had lived in a trailer while rebuilding and spent many weekends helping with one of the valley’s replanting projects. He still spoke fondly of Kansas, but never mentioned going back there anymore.

Mister Glass picked up one flashlight from the floor of the van, gave his other to Aunt Jenny, and then we began to walk to the other vehicles that had been parked along the road. We spread out a little, but stayed within sight of each other’s lights. Personally, I kept a hand on Claire’s shoulder, telling myself it was for her comfort and safety but knowing it was mostly for my own peace of mind.

The other lumps were just that: lumps, which was an extreme relief. It seemed that everyone from our work party except Annie Meyers had made it into a vehicle. While some people were still having trouble breathing, they were all still alive. As word went around, people began to point fingers in regards to Annie Meyers. Why hadn’t anyone helped her to a car? Why hadn’t anyone looked for her?

“Wait,” Claire interrupted. “How did Annie get here?” Several people grumbled in reply, but Claire stood firm and asked, “All of the rest of us scrambled for the vehicle we came in, right? Who did Annie ride with to get here?”

At varying speeds, we all came to the idea that Claire’s question was a good one. We didn’t immediately have an answer until someone declared, “The Roxons!” As several people, me included, said something interrogative as to what the speaker meant, he (Freddy Wilson) said, “The Roxons were working with us earlier today. Were they still here when the storm hit or had they already left?”

Everyone spoke but no one could remember when the Roxon brothers left, whether Annie might have come with them, or whether she was friendly enough to have ridden with them in the first place. A couple people said they thought they had heard a car moving along the dirt road in the early moments of the storm, but they weren’t for certain and other people were sure they hadn’t heard a vehicle. Someone said, loudly, that it would be just like the Roxon brothers to run off and leave poor Annie to die as they took care of their own skin. Others argued that the Roxons wouldn’t have done that. I stayed silent, remembering how my own moment of selfish panic had only been thwarted by the happy accident of my sister beating me to the truck. I said a prayer of thanks in my mind that I had found her, for if I hadn’t, she might have suffered Annie Meyers’ fate.

Someone said something about how it must be one whale of a forest fire, to be interrupted by Danica Frowley, who said in a tone that brooked no argument, “This is volcanic” as she rubbed (apparently) ash between her fingers.

Someone objected, “We don’t have volcanoes around here!”

Danica happened to be looking at me as she said, “I didn’t say it was around here. It could have come from a hundred miles away, or a thousand. But no forest fire is going to produce this amount of ash—look at the places we’ve been working these last couple years. Somewhere, maybe Capulin down in New Mexico or Krakatoa in Hawaii or one of the Alaskan volcanoes or—somewhere, a volcano blew.”

“This came from the west,” Mister Glass pointed out. “Does that mean it was Alaska?”

“There are volcanoes all along the Pacific rim,” Danica told him. Danica Frowley was a banker from nearby Fairplay who loved to hike in the woods. In her mid-thirties and fairly attractive with her flawless dark skin and lithe frame, I had heard more than one person wonder why she had never married. I had gotten to know her a little on these weekend work parties, but not well enough to have any sort of answer for that question. I had a guess that she was married to her work, but that might have just been nothing more than a guess. “And just because we saw the ash coming from the west doesn’t mean the volcano is in that direction. Did you see how high that wall of ash was? I think it came from the west, too, but at that altitude, the winds can blow differently than—“ She shook her head and said, “That’s neither here nor there. I can’t tell you where the volcano is, but I can tell you this much ash has to be volcanic.”

Since she seemed to know what she was talking about, and as none of us had any better ideas (and agreed with her assessment that this level of ash was beyond any of the fires we had seen in past years), we all turned to her as our authority. “How bad?” Claire asked, receiving nods of agreement from many of us.

Danica thought a moment, then replied, “Depends on where this happened. If we’re right and this came from the west—probably from the Pacific Rim—if it can blow up there and hit us with ash here … then I would think we’ve got to be talking a death toll in the millions.” As we all mouthed the words—twenty-plus of us standing around her—Danica continued, “Seattle, San Francisco, if they were closer to the blast they might be leveled now. And if this set off the San Andreas … “

Aunt Jenny looked at her watch and said, “We felt that first quake at about five-fifty, our time. It was probably, what? Better part of an hour before the wall of ash hit. Then, it was almost five hours before the ash let up enough for us to get out of the vehicles. Does that tell us anything?”

Danica answered, “I have a cousin who’s a geologist. It might mean something to him. I have no idea how far or fast a wall of ash like that could travel. And if there’s a weak spot in the earth’s crust, that might not be the only volcano—others could open up or it might just be the one. Either way, I don’t think this is a good thing.”

“Well,” I said, speaking for the first time in a while and finding the nerve to do so I knew not where, “It seems to me that the thing for us to do now is try to get back to town or to our homes. See if there’s power there and if anyone’s hurt.”

Several people agreed, but someone asked, “What about Annie? Do we just leave her here?”

“Somebody help me get her into the back of my truck. I can take her at least as far as Como.”

“And then what?” Claire objected. “Put her in the barn until someone claims her?”

“It’s either that or leave her out here,” I replied. Did I mention that, as brother and sister, we were often very skilled at pushing each other’s buttons? In the past, we had just been better at keeping it off public display. Of course, we had never had one of these discussions over a dead body before, either.

Claire, in an overly-logical voice I had come to hate over the years, said, “We can either take her into town and bury her or fire up the front end loader over there and bury her now. Either way, the salient point is that she’s dead.” That last word was said with pointed irony that deserves its own special typeface.

“We’ll take her in the truck,” I pronounced somewhat imperiously. “She was Catholic. We can take her to the Catholic Church in Como. Probably people gathering there right now, trying to figure out what to do next.”

Claire clearly wanted to object, but she didn’t interfere when a couple ladies wrapped Annie Meyers in an old blanket and then myself and Freddy loaded her into the back of the pick-up truck. It suddenly registered on me that I was going to be driving around with a dead body in the back of the truck and I wasn’t crazy about the idea but I wasn’t going to tell my sister that. What I said to her was, “Come on. Sooner we can get to the church, the sooner we can get her out of the truck.”

Claire said nothing in response, but got into the cab and slammed the door.

I was relieved when the engine fired up, though I had no reason to think it wouldn’t. I turned on the headlights, but that actually reduced the visibility due to the ash still in the air. I turned off the headlights and switched on the fog lamps and that helped some. I looked in my rearview and saw several other vehicles turning on their lights. I was glad I had parked with the truck pointing down canyon as I watched people behind me do three point turns on the narrow dirt road.

“Why aren’t we moving?” Claire asked, none too happily.

“Just making sure everyone can get their wheels going,” I replied as I slipped our truck into drive.

As we moved out slowly, Claire surprised me by saying, “I’m sorry I argued back there, Josh. I just—I just—I don’t know. I just get a feeling way down in my stomach that Annie’s not the only one who died here this evening and, well, maybe if I can deny she did, maybe no one else did, either.”

“Yeah. I understand.” I looked over at my sister in the glow of the dash-lights before us and headlights behind us and asked, “You think Miss Frowley’s right? Millions dead?”

“Dear God, I hope not,” my sister replied quietly.

At the mouth of the valley, where it opened out onto the larger South Park Valley near the site of what had been the town of Peabody back in the gold rush days, there was less ash. As if the valley we had been in were a large pipe that had blown the ash away from its entrance. But then, as we passed onto the grounds where once had stood the other mining town of Hamilton, the ash started getting thicker. By the edge of Como—itself once a prominent mining town but by this time a burg with an official population of less than fifty people—the ash was six inches deep and, like snow, drifted higher in some places. I was only going about five miles an hour—at the beginning due to visibility but then because the traction was so miserable. I had driven that old truck in snow storms and on ice, but driving on that ash was the least in control I had ever felt in a vehicle. Only a mile down the road and I could already feel the ache in my shoulders from the tense way in which I gripped the wheel.

And then someone started honking their horn and flashing their lights behind us. I came to a stop, panicking for a moment as it seemed like we were just going to keep sliding indefinitely, and then got out. Mister Glass had been right behind me in that old conversion van of his and he was getting out as well. We had started out from the Selkirk with six vehicles in our caravan and now there were only five. “What happened to Miss Frowley and her bunch?” I asked, as if Mister Glass could somehow know more than I did under the circumstance. Rather than snap back pithily, he just shrugged and we started working our way down the line.

At the last car, driven by Freddy, we were told, “I just looked up and Miss Frowley wasn’t behind me. I didn’t see her go off the side or anything.” Freddy was getting out of the car as he said this and began walking back down along the road.

Mister Glass had had the presence of mind to grab one of his flashlights and began to sweep the road and the ditches to either side. We had only gone a couple hundred yards when we found Miss Frowley and the three people with her gathered around her car, the hood up. As we came up closer she said, “I tried honking, but I wasn’t sure if anyone had heard me.”

“What happened?” Freddy asked her.

“Just died on me. I can’t get it started back up.”

Freddy motioned for her to get into the car, then said, “Try again.”

The car made a chugging noise, but wouldn’t engage. Freddy opened up the air intake, took out the filter, and looked at it in the light of Glass’s flashlight. “Full of ash,” Freddy commented, banging the filter against the engine block. Putting it back in place, he motioned for Danica to start the car again. She did, and it came on, but still sounded sluggish.

“This is going to be a problem,” Freddy commented sardonically, to be punctuated by the sound of one of the cars ahead of us honking wildly. As we three set out at a run, Miss Frowley’s passengers jumped in her car and followed us.

The third car in the caravan had been driven by Wlllard Guthrie, who was now standing beside his car and peering under the hood. “Just died. Acts like it’s not getting gas.”

“It’s not getting air,” Freddy told him, and us. “And who knows? The gas line may be clogging up, too.” He looked around and said, “There’s a good chance none of us are going to make it very far this night.”

“Well, let’s go while we can,” Mister Glass said, then we could hear his van dying from where we were. At that moment, Danica pulled up even with the convoy only to have her car die again.

Available now on Kindle and in paperback and hardback!

5233 A.D.

Soldiers sent on a mission of diplomacy from their king are murdered. Was it an ambush by the mysterious enemy to the south? Did the king himself have them murdered? How did the survivors make it back alive, and will they be allowed to stay that way?

Elo has found her nephew and a family beyond her reckoning. They are numerous and friendly and share her faith … and possess technology beyond the dreams of the people on the plains. Yet it is not paradise, for beneath the surface in those cold, snowy mountains is a past no one wants to recall.

And John. He is becoming a man, with a man’s ambitions and desires, but is forever haunted by the mother he never got to know. Even if he wanted to forget her, he is constantly reminded—by seemingly everyone—that he is Noiné’s child … and her prayer.

Sample reading

“Hard to breathe up here, isn’t it?” said the older man to the younger.

The younger, in his youthful pride, had been trying not to admit to that difficulty but since the other had brought it up was less embarrassed to say, “Yes.” He wanted to say more, but at the moment he could not. He stopped and tried to fill his lungs, but was not as successful as he would have liked to have been.

The two sat down on a rock, the summit in sight but not appearing to be that much closer than the last time they had stopped. The younger man told himself he was stopping so often for the sake of the older, but in his heart he knew that he was stopping because he was out of wind.

Why?

He was pretty sure he had climbed mountains this tall before. Had they given him such trouble and he just didn’t remember it?

And how was the older man making it at all?

Maybe it was just the temperature, for it was—if not cold—brisk. And the little bits of wind that blew by seemed like they were taking away what breath he had.

“Not much further,” said the older man, standing up and gesturing towards the summit so tantalizingly close.

As the younger man stood up, he asked himself just how old the older man was. Fifty? Sixty? He had been told that such numbers didn’t mean much, and had met men and women both who were much older than those numbers. They generally didn’t walk so far and climb so high, though, seeming content to just stay near their own front porches.

Still, the older man at times didn’t look all that old. For most of this trip, in fact, he had been the first to set out and the last to stop, taking the steps—even the steep ones—with a spryness to his gait the younger man had to think about to match. On horseback, few could match him.

Yet other times—as when they sat by the fire the night before—the older man could look even older than usual. Had it just been the firelight highlighting the deep lines in the old skin? The younger man didn’t think so, for he had noticed similar appearances at other times.

But did not everyone have such times? Times when they didn’t know (or care) they were being watched and their mind had gone back—back to where? Probably different for each person, he reasoned. Some remembered an old romance, or an old homestead, or a missed opportunity. Many remembered friends who had passed away or perhaps just gone away. In that moment, more cares than usual piled up on the countenance, making the person look older and much more careworn than they were. Or, maybe it was the person seeing who had gone away, leaving behind someone they now wished they couldn’t see.

Was that true of his old friend? He knew to a certain extent it was. The man spoke of many things he had left behind—some of his own volition and some just because he had to, forced by persons or circumstances. Perhaps the man was even younger than his young friend thought but had so many such remembrances that they had worn grooves in his countenance.

His old friend, he thought as he watched the man’s steps eat up the mountain side as if it were nothing, had many cares that might have caused the marks. While the man had never seemed shy about sharing all he knew with his young friend, surely he kept some things to himself. And maybe those things didn’t necessarily wear on him, but led to a pensiveness now and then.

The younger man realized suddenly that, in his reverie, he had allowed the older man to gain on him and quickly began to make up the space, his youthful pride unable to allow anything else.

As they neared the summit of their hike, a sort of bench between two mountain peaks, the younger man began to realize that not all of the giant shapes on the ground were boulders, though they were rocks. Some of them had been carved at one time, but what they had been in the shape of he did not at first know.

Then, he saw what appeared to be a carving of a hand—larger than his own torso—holding on to something. What had it been holding? A sword hilt? A walking stick—such as he used himself?

He was about to ask the question, when he realized that some of the other carven rocks he could see must have been a part of the same statue. A shoed foot here, another hand. Most of a britches-clad leg. A very large rock that might have been a torso, carved to look like someone wearing a fur coat with a prominent collar. And then a third foot.

Then, as they reached the summit, he saw a cleared off space. Not just cleared, though, but smoothed by some sort of concrete or like substance poured between the boulders to make a flat space. There were giant footprints on the flat space, where the statues must have stood, leaving imprints where some of the flat had been pulled up—and one part of a giant carven shoe.

The older man stepped up on the flat space and—rather than looking around at the magnificent alpine vista, looked at the space as if he could … what? See through it to the mountain as it looked once before? Then, he was looking up somewhat, but still appeared to be focused primarily on the detritus of the statues, which stretched out across the tundra to the northwest.

“These statues,” the younger man asked, once he had his breath and was standing near his mentor, “Who were they of, Papa?”

The older man smiled, for the younger had called him that since childhood, and replied, “There is something of a debate about that, Son. There were, it is said, two statues, one of a man and one of a woman. They were perhaps attached—one ancient drawing I have seen shows them holding hands—so one might argue it was a single statue. As to who they were, that is where the debate comes in. It is generally agreed among all historians I have read that the man depicted was a forebear of the mountain people, named Josh.”

“And the woman?”

“That is where the debate is,” the older replied with a smile. “Some say the statue was of his wife, but others say it was of his sister, for both figure prominently in the history of the mountain people. The only agreement is that the man was Josh.”

“You have spoken of him. He was not actually the founder of the family, but he carried them through a hard time, didn’t he?”

The older man smiled and said, “You have a good memory, for I believe it to have been very long since we discussed such things.”

“Yes,” the younger replied, though it was somewhat unclear to which statement he was agreeing, perhaps to both.

“Yet, as I have thought about it, I think the credit should go to Josh. His forebear, John, may have named the family, but it was really Josh who set them aside. And who brought the name of the mountain people not just to those of bloodline, but to all those under his care.”

“Still, I like to think that John was the founder,” said the younger with a smile.

“You would,” the older man replied with a chortle.

“So who built the statues, and who tore them down?”

“There is some debate as to the answer of those questions as well.” He took a deep breath of the thin air, then said, “Look. Just look. We can have questions in a moment.”

The younger man almost bristled as he had as a child, but had learned to express some patience with his mentor’s style, but also to enjoy the brief return to the old words, for how many times had the older man said something so like that while teaching?

Where they stood was spectacular. They were not actually on the summit of the mountain, but something of a saddle between three summits, one which was probably a hundred feet higher than where they stood and the other four times that much—the third summit shorter than both, which had allowed it to be hidden as they approached. Snow still clung to those peaks in little patches. Around them in every direction, they could see peaks and valleys, rivers and lakes, as far as the eye could see. It was a mountain panorama to take one’s breath away if the elevation hadn’t already done so.

It was worth stopping to look at, the younger man admitted to himself. Over there, to the north, some of the peaks still had so much snow it looked like they were still in winter. In the valleys below—in every direction—there were green fields and the pale white trees were spreading their shimmery green leaves. And one could catch a bright sparkle of light reflecting off cascading water from miles away—in some cases from streams that were so narrow the young man could have jumped over them, but they were at just the right angle to catch and reflect the light like a diamond dropped from the stars.

They had stood there like that for many minutes before the older man bade, “Come, let us see if we can find something I was told about that might answer your second question, if not the first.”

It took the younger man some steps before he remembered what his questions had been.

Across the mountain they went, though not straight down, angling to the northwest to follow the path of the debris. Aiming for what appeared at first to be a more ovoid shape than the other pieces they could see, they neared it and the younger man asked, “Is that a head?”

As they got closer, the younger man could see that it was, indeed, a head hewn from rock. While the features had never been intricate, it was clear that it had been the head of the female figure. Her hair had been tied back in a bow, though the hair which emerged from that bow had been broken off at some point. The younger man glanced around and thought he saw a rock that might been the hair—or part of it—but he wasn’t sure.

“Look,” said the older man, “At her face. The smooth cheekbones, the simple nose, the faint smile on her lips.”

“She looks … almost happy laying there,” commented the younger man.

His mentor nodded and then said, “Now, look over here. Just where I was told.” He pointed to another ovoid rock, not far away. They stepped up to it and found another proud face, laying sidewise on the ground, looking pleased. There was a crack in the face’s nose, but otherwise it was in good shape.

“That must be Josh,” said the younger man, to which the older nodded. “So, was the other his wife or his sister?”

“Does it matter?”

“It did to them,” the younger man said with a laugh.

The older man laughed, then said, “I suppose it did. Personally, I think the female statue was of Josh’s wife, whom they name Adaline in the old stories.”

“Like the people who take care of the sick and help doctors?”

“Yes. That order is probably named for your ancestor.”

“I always wondered where that term came from. I’ve heard of Josh, but never Adaline. Wasn’t his sister named Clara?”

“Claire, I believe.”

“So who built the statues and who tore them down?”

The older man nodded, then thought a moment before saying, “It is believed that the mountain people themselves built the statues, descendants of Josh and Adaline—or Josh and Claire, his sister, for she is said to have not only had many children, but to have been just as much of a leader in the early years as her brother. As to when, I have read many scholars and they believe the statues were built about a thousand years after Josh actually lived. They were torn down about a thousand years later, perhaps twelve hundred years later.”

“I do not remember tales of there being wars then,” the younger man injected.

“There are always wars,” said the old man sagely. “But you are thinking as I am. You see, there are many among the mountain people who come to this spot—as something of a pilgrimage—and many hold that the statues were torn down by the people of the plains during one of the wars. But if the timing is correct—whether eight hundred years ago or a thousand—there is no record of warfare between the two peoples just then. In fact, in most stories there was said to have been about five hundred years of peace and relative cooperation during that time as they banded together to protect from an enemy from the north.”

“Who, then, tore the statues down?” pressed the younger man.

“Look at this head.” Then he walked uphill to the first head they had come to and bade, “Now look as well on this head. I want you to notice something very specific about both.”

The younger man walked all about both heads, then stood partway between them—but a little closer to the woman’s head—with his hands on his hips. Finally, he admitted, “I do not know what you want me to see.”

The older man walked closer to the statue of the woman, the head that was twice as long as he was tall, and said, “Imagine you are the enemy. You have come all the way to this spot, across rivers and mountains and past countless enemies. You arrive at the statue of your hated enemy’s forebear. What do you do to such a statue?”

“You tear it down,” the younger man answered, as if speaking the obvious.

“Correct. You tear it down and, then what?”

“Go on to fight the enemy. The people who are your enemy.”

The older man shook his head and said, “Think of what it took to get to this point. You want to triumph over your enemy by casting down his heroes, correct? You want to show your triumph not just to the people of the day, but to anyone who might come back—especially anyone who might come back with the hope of rebuilding the statues.”

After several minutes, the younger man shrugged and—just a little bit petulantly—said, “I do not see what you think I should.”

“If you were a warrior and had chopped off the head of your enemy’s king, what would you do with that head?”

The younger man wanted to bristle, tired of being “taught” but managed to say, “Throw it away?”

“Yes. But if you are like most soldiers throughout history, you wouldn’t just do that. You would use it for a football if it were much smaller, you would throw it in a pond, or perhaps take turns striking it.”

The younger man was trying to figure out what his mentor was driving at while still bristling and telling himself he was too old to be taught this way when it suddenly came to him, “If these statues had been blasted by an enemy, or even pulled down with ropes, the heads would have rolled much further away, or they would have been broken to pieces—the ears and noses chopped off. Foul scribblings carved into the very rock.”

Seeing the older man nodding proudly, the younger man hypothesized, “Whoever took down these statues, respected the heads. They respected the memories of Josh and Adaline—or Claire. Why? Why would they do that?” He paused, waiting for an answer, then said, “They were not enemies of Josh and Claire, or Adaline. They were … who? Mountain people? If so, why would they tear down the statues?”

The older man led the way over to a rock about midway between the two heads—a rock that didn’t appear to have been part of the statues—and motioned for the younger man to sit as he did the same. When seated, he chided, “Though you don’t seem to remember their names, remember what I taught you about Josh and Adaline, and even Claire?” As the young man nodded, he continued, “Does Josh seem like the sort of person who would have wanted a statue in his honor?”

“I can’t claim to know that much about him,” the young man said with a laugh.

The laugh was shared, then the older man said, “Think about who Josh and his sister and his wife—and his sister’s husband—served. And all their children, and the others they gave their name to. Did he not say, ‘You shall have no graven images before me’?”

“But they didn’t worship at these statues, did they?” the younger man challenged. “They were just to honor the forebears, weren’t they?”

“I believe so. Still, I think two things happened over time. While people might not have worshiped these statues, some came here thinking more highly of who they represented than they should have. You know the stories. Josh and Adaline were not perfect. They were leaders, but not saviors—”

“There’s only one of those.”

“Precisely. I think there was a movement among some of the mountain people to think more highly of their founders than they ought. That was the first thing I believe happened. The second thing I believe happened was that some of the descendants of Josh and Adaline realized this so they took the statues down. Yet, they couldn’t bring themselves to despoil them, for they honored their ancestors as well.”

“So they took down the statues, but left the heads intact? Why?”

“You, more than anyone else, should be able to understand.”

The younger man wanted to get angry again, but managed to say, “But I do not.”

The older man smiled warmly and said, “You know all the stories I have told you of your mother. You want her honored, but do you want her worshiped?”

“Well, I—”

“What if someone were to build a statue in honor of your mother and start to worship that statue, or just give it more reverence than what your mother stood for. Would you not try to stop them? To change their minds? To tell them the truth about your mother and who she worshiped?”

“I, um, I suppose.”

“What if you were to rush into the town square and take down the false idol erected to your mother? You tear it down just as you believe she would. Yet, it is carved to look just like her. Could you bring yourself to despoil her face?”

“I—” the younger man started to say one thing, then exhaled what little breath he could gather and nodded, saying, “I think I understand. That’s what happened here?”

“It’s what I think happened here,” said the older man with a smile. “Some of the mountain people still say it was enemies who tore down these statues, and I suppose they could be right though no one knows for sure. It is just my thought that that those who tore down the statues did it to honor Josh and Adaline—or Claire—just as those who built the statues had set out to do.”

After a bit, the younger man said, “That does make sense. I think you’re right.” After a bit, the younger man asked, “I saw a giant hand when we were first approaching the place where the statues stood. It appeared to be holding something, but I do not know what. Do you know what the statue was holding?”

With a shrug the older man replied, “Not for sure. I have seen drawings, though none were made by people who had actually seen the statues. Some were purported to have been made by people who had talked to people who saw the statues, though that is in doubt in most cases. Some say that Josh was holding onto a sword, but I found that doubtful for there is no reliable story of him ever using a sword. There is one prominent story of him using what we would call a percussion weapon—”

“I remember that,” the young man said excitedly. “When he shot the man who had tried to attack his sister.”

“Yes. But whatever was in his hand didn’t look like any sort of percussion weapon I’ve ever seen. It might have been a plow handle or a hoe or some implement like that. I find that most likely, for he was a mighty man of the soil, as most of his descendants are now.”

“Do we know for sure it was Josh’s hand? What if it were Adaline’s, holding onto some sort of medical implement? She was a doctor, wasn’t she?” he asked, the story about her coming back to him. Why had he not remembered her name? he wondered.

“Yes, she was. I have never seen a drawing depicting such, but you could be right.” He smiled and said, “I like to think you are right, that it was her hand, not his. Doctor or farmer, what made Josh and Adaline memorable—or Claire, who was said have been a seamstress as well as a mother—was their faith and their overarching hope in the future. As the world was falling apart around them, they were said to have clung to their faith—the faith you share with them—to see them through.” He patted the younger man on the shoulder and said, “I like that idea. Perhaps she was holding some implement a doctor of her day would use. Bringing healing of body and soul to the people.”

The younger man nodded, then prompted, “You say it’s the faith I share with them. Do you still not share it with us Cyro?”

The older man smiled and replied, “I do, but sometimes I am like some of those people who came to worship at these statues. I forget to worship the God the people depicted worshiped and find myself only honoring your mother.”

“She would not want to be worshiped.”

“I know that,” Cyro said with a wan smile. “On the other hand, the faith she showed me was the most genuine thing I have ever known—save perhaps your faith. I spent many years denying that faith—any faith—and that is a hard habit to rid oneself of.” He stood up suddenly and said, “We will speak of this more. But first, John, let us find a good place to have a fire and a camp for the night for it will be most cold up here after dark.”

Order it today for Kindle, paperback or hardback!

(Published Aug 13, 2022)

5225 A.D.

…

It has been three millennia since the last of the great wars.

Two thousand years since mankind emerged from the little pockets they had fled to, trying to avoid the poisons.

Ancient tribes, politics and allegiances are all forgotten. Science? Religion? Philosophy? Engineering? Gone. Forgotten. Without a trace.

…

In the aftermath of the murder of her family, Noiné emerges from the ashes of her home, clinging to an ancient and mostly-forgotten faith and determined to make things better for herself, the child she hopes to have, and the sister who may yet live.

Sample Reading

Noiné was seventeen when the raiders came.

She had been out in the fields, in a little depression that made her invisible from the house. On such days it was hot—not just warm, but hot—yet she still liked to go there when her chores were done for it was the closest thing to solitude she could find in her life. No parents or grandparents and, especially, no siblings. Just far enough away that she could barely hear the normal goings-on of the farm, but close enough that she could hear should someone call out.

She liked a little time alone now and then. She wasn’t quite so enamored of solitude as her nearest sister, but she did like to take a few moments now and then to just revel in silence. A person from the city might have said she lived always in silence, but Noiné didn’t think so. There were always the noises of a farm: the clink of metal, the stomp of hooved feet, the turning of the windmill. Add in the noises of her youngest siblings, who never stopped talking! and it became overwhelming at times. She would move off to where she could hear if called, but have a little peace. Sometimes she prayed, sometimes she sang little ditties and hymns to herself, and sometimes she just sat and barely thought about anything.

Therefore she heard the scream.

Noiné popped her head up cautiously, thinking her mother had perhaps seen a mountain lion and not wanting to draw attention to herself from the cat as she was so exposed. What Noiné saw was a handful of men on horseback, attacking the farm. One of them was riding away with Noiné’s mother across the saddlebow in front of him. She thought she saw her father—or maybe her father’s father—lying facedown in the yard. She saw her grandfather—her mother’s father—try to charge the raider carrying off her mother and receive the lead from some sort of percussion weapon full in the chest for his troubles. He slumped to the ground and moved no more as Noiné watched.

Noiné was too scared to make a sound. She lay facedown on the prairie grass, feeling its warmth against her skin, and wept as silently as she could. When she could get her hearing back, she lay still, listening for sounds from the farm. There were still hoofbeats and footfalls, though no more screams. And then she heard the crackle of flames and each pop was like seeing her grandfather shot again. Her heart heaved in her chest and she was afraid she would make a sound that might be heard. It seemed to her as if her heartbeats could be heard!

Would that be so bad? she asked herself. Wouldn’t I rather die with my family than survive alone? A voice inside her head told her she was a young woman, thought pretty by some, and the men who would carry off her mother would do the same to her and worse. She clutched at handfuls of the prairie grass as she thought of her mother. She prayed her mother could escape.

Or die quickly.

Her wits returned in conjunction with the setting of the sun. She left her little depression and made her way to a nearby draw, hunched down and, hopefully, unseen. Once in the draw, she made her way towards town. It was all of six miles and likely seven, but she was sure she could make it—even if it turned dark before she could get there.

The dress she wore was a light brown, simple thing, which would help her blend in with the surroundings as the sun sat. Her long brown hair she had twisted into a single braid down the center of her back, as was the custom for a woman of her age among her people. She fingered it lightly as she set out, the feel bringing her both comfort and sadness for her mother had braided it for her. For the last time? she wondered.

She had only gone a few steps when she turned back. She crept back to where she had been hiding and peeked over the roll in the fields. There was no movement around her house, and her house itself was just a smoldering ruin. In the fading light she could see the lump in the dirt where her grandfather had fallen. She saw another, similar lump near the ruins of the barn and had to cover her mouth to keep herself from making an anguished sound aloud. She felt the sound in her throat and chest, though.

Noiné topped the small roll and made her way to the remains of the house. When she was close, she whispered the names of her siblings but heard nothing in response. Where were they? In the house? Had they been taken by the bandits to be sold as slaves or something even worse? She stepped over toward the barn and saw that the lump was her grandmother, and near the barn her other grandfather. She wanted to fall down into the dirt and lay there with them until she died, but her legs continued to walk as if by their own volition.

She found no sign of her father. She guessed him to be wherever the children were, for he would have protected them to his last breath. How would he have done so? He was not a fighting man. Strong, resolute, and a harder worker than any two other men, he would have fought back with his hands if he could. He might have retreated to the corn crib, which was close to the house but had solidly built walls. She had a vision of him trapped in the house with the little ones and suddenly it became clear: if that were how he died, while the house burned and crashed around him, he would have been holding her siblings close and saying prayers over them and telling them the stories of their family’s faith that he knew so well.

She made herself stop and say one of the prayers he had taught her and her siblings. It gave her a little strength, and then she began to walk. Five miles to town? she asked herself. More like seven, she thought. And she had never made the journey in the dark—she had made it rarely enough in the light. But she was convinced she could find the town. Would she find help? Her family had never been shunned in town, but neither had they been regulars, coming in only twice a year: once to buy seed and once to bring in the harvest. Even doctoring, they did themselves.

They were not without friends, though. There was the family named Trook to the east, but that was in the wrong direction. And what if the raiders had hit them, too, for the one who rode off with Noiné’s mother was heading that direction.

There were other farming families they were either friendly or acquainted with, but were mostly in the wrong direction as well. The ones that weren’t, were off the path if she were to make straight for town. Oh well, she thought, maybe I’ll at least see one of them if I somehow get off the track.

An hour later, she was sure she was still on the right track but was wishing she had brought some water. She thought she recognized some of the landmarks even in the wan light of a fading moon, and thought old lady Deen’s farm might be nearby—and she had a good well, one of the best around—but Noiné was afraid that if she got off the track she might not find it again. And she had seen no lights on the horizon to indicate a campfire or even a lantern, so the path seemed her best bet.

She had cried much that first hour, but then it slowly faded and she just became an automaton, putting one foot in front of the other, thinking of nothing except staying on the path—which she imagined looked rather silvery in the moonlight. At least, she prayed what she was seeing was the path. She wasn’t sure what anyone she came to could do, but she just kept telling herself she had to make it. When her mind began to get numb with the exhaustion and darkness, she kept herself alert by reciting the prayers her parents had taught her. She even smiled as she realized that she was subconsciously saying the prayers to the cadence of her footsteps and, if she wanted to increase or decrease the speed of one she had but to increase or decrease the speed of the other.

She did. Her shoes—which hadn’t been much to start with—were torn and her feet were bleeding when she finally came to the outskirts of the little village the locals called Forest (though the forest it was named after was little more than a few old, gnarled, wind-blasted stumps anymore). She had fallen once—she wasn’t sure why—making her clothes dirty and the palms of her hands wet with blood and sweat. She had a tear near the knee of her skirt from the fall but she told herself to be thankful for that because it let a little cool air in on what was a surprisingly warm night.

She had run almost mindlessly at first, then settled to a walk when her lungs and side commanded her to, not knowing what sort of help she might find in town for her family only had the minimum amount of contact with the people there. Noiné knew why that was, but also knew to not talk about it, even within her family. Still, she hoped there would be someone there who would be willing to help, for weren’t the raiders a problem to all?

As she approached the town, she wasn’t sure where to go, but then she saw a slew of horses tied up before one building and decided with what was left of her mind to go there. Some men were standing around on the porch before the building—which she thought might be a public house of some sort—and one of them made a half-hearted effort to stop her as she burst through the crowd and into the building.

Inside, before her eyes even adjusted, she called out, “I need help! The raiders have attacked my family.”

Someone nearby put a hand on her arm and said something like, “You need to get out—”

But then a voice spoke from the middle of the room and all other sound disappeared. “What is the problem, young lady?” a voice of command asked. She looked and as her eyes adjusted to the dim light and the dark paneling inside, she saw a tall man standing up and coming toward her. As he stepped into the light she saw that he was a man of regal bearing, taller than most and with a strong face. He reached out to her with large hands, which she took nervously and found them calloused.

She said, the words flowing quickly, “I live just northeast of town, about seven miles. Raiders attacked our farm. I saw one of them carrying off my mother. I saw my grandfathers laying on the ground, dead. I—I ran.”

The man came closer, then commanded someone to his left, “Get this young woman a drink, and food if she can take it.” He helped her to a chair and asked her in kind tones, “Now tell me exactly what you saw and how we may get to your place.”

Noiné took a sip of the proffered drink, then related all she had seen—little as it was—and directions on how to get to her family’s farm. The man listened intently, then turned to another man who stood nearby, a man with the darkest skin Noiné had ever seen, and said, “Yarfan, I want the men mounted up and ready to ride now.”

“Understood, my lord,” Yarfan, the dark and very thin man who nevertheless looked to be made of long muscles, said. He turned smartly on his heels and followed his men, who were already heading outside.

The man who was clearly the leader took one of Noiné’s hands in his own and said, “Rest assured: we will find who did this.”

“May I—may I ask who you are?” she managed to reply in timid voice.

He smiled, a very nice and warm smile, and told her, “I’m the king” with a good-natured chuckle. Then, standing to his full height, he turned to a stout woman nearby who was apparently the keeper of the inn and said, “Take good care of this young lady. Provide for her needs. I will be back and will settle up for her expenses as well as our own.”

“Yes, my lord,” the innkeeper said, nodding obsequiously.

What if an inventor, say an Edison or a Leonardo—instead of sixty—had eight hundred years to invent? What if the antediluvian world were not made up of hunter-gatherers and the beginnings of an agrarian society, but of spacefarers and scientists?

And what if it were into a world like that that God spoke to tell one of the preeminent scientists of the day to build an ark of wood?